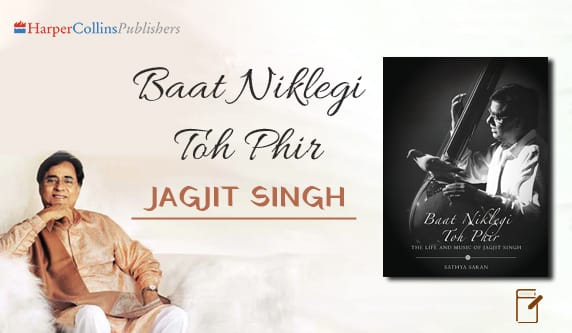

Jagjit Singh, the ghazal king of India, was a singer, composer, arranger, lyricist, all rolled into one. Besides which he was a brother, friend, husband, and above all a father.

I was in my second year of college when suddenly the tv in the activity room declared the untimely death of Jagjit Singh. It was 10th October 2011. I remember the moment as more than fifty boys came to a complete standstill for a few moments.

Hum labon se kah na paaye…

The sound of a Jagjit Singh song, playing on a speaker afar, broke the silence. The crowd slowly dispersed, leaving space for silence behind.

Jagjit Singh, a Professional Par Excellence

Jagjit Singh never hesitated in saying no to impromptu song requests as he was quite aware of his stature. Not that he was bloated on ego, but clearly the voice with that heavy bariton commanded respect.

Why I bring this up now?

Because it was the sheer respect for Jagjit Singh that silenced each one of us on that day. Not a single cuss word came out of anyone’s mouth which is usually the vocabulary of an undergrad.

Jagjit Singh found the strange mix of admiration and reverence from the generations olden and new. His voice still conjures up as much warmth of love as it used to during the 70s or 80s.

Jagjit Singh, a Timeless Figure

Jagjit Singh would have turned 80 today, had he been alive. But then again, when have the artists cared about the time and its limitations.

Whenever Jagjit Singh asked, the audience sang. He used to get them so involved in his performances that people used to feel intoxicated on love and a time long gone. His calling was the most authoritative yet the softest.

Timeless is not he who survives the tests/passage of time, but the one who summons it at his will.

Baat Niklegi toh Phir: the Life and Music of Jagjit Singh

The biography of Jagjit Singh, Baat Niklegi toh Phir: the Life and Music of Jagjit Singh traces the evolution of the artiste from his Namdari Singh roots through his diverse musical influences to his recreation of the ghazal as a lively, contemporary form of music that could hold both the young and old in thrall. From the days of singing ad jingles to his breakthrough album, Unforgettables, to his soul searching music for Gulzar’s Mirza Ghalib, from his love of music to his fetish for horses, from his marriage to Chitra Singh to his tryst with spirituality, this book tells the story of the most loved ghazal singer of our time with great sensitivity. Delving into Singh’s personal triumphs and tragedies, Sathya Saran presents a man loved by many, revered by some and unsurpassed as yet in his chosen field.

An Exract From the Book:

CHAPTER 5

The Victoria Terminus Station in Bombay is a landmark for tourists. Declared a World Heritage building by UNESCO, its mind-boggling mix of Gothic and Indo-Saracenic architecture has visitors and the occasional local standing in awe as they take in the leaping gargoyles and the perfect dome with the statue atop it. Today, Bombay has become Mumbai, and other rail hubs have been developed for outstation trains to terminate at.

But in 1965, when Jagjit Singh stepped out of the Pathankot Express as it steamed into the terminus, he must have, like a million others before him, been swamped by the immensity of the place, as much as by the crowds that thronged the platforms.

The young man however was by now familiar with the city. Preferring comparatively cheaper and quieter lodgings to his earlier hotel near the V T Terminus, he found a small room, in Gope House near the Elphinstone Road station. Within days, his easy camaraderie and friendliness had won him a small circle of friends. But life is never easy in any city for a newcomer with slender financial means. And Bombay is a relentless, cruel metropolis that keeps her own beat, rejecting those who cannot keep step with it, rewarding a few who manage to accept her demanding ways.

Jagjit found himself adrift in no time. Thrown out of the tiny room at Elphinstone Road, he found accommodation in the Sher-e-Punjab hostel in Agripada. It was crowded and dirty, and a far cry from the clean and meticulously run home his parents kept, or even the college hostels he had inhabited; but he had little choice. Moreover, his entire concentration was in making it as a singer. This then, he thought, must be just a rite of passage. He took it in good humour, even joking wryly about the bed bugs who grew plump and shiny feeding off the floating population who occupied the four cots in the room, and the fact that one night a rat took a bite off his heel, the room was blessed with ‘room service’. A teashop stood just below it, which he could call down to, for room service and bed tea.

Still chasing his dream, Jagjit would take the local train as it rattled emptily in the evening towards Churchgate where it would load on the working millions heading back to their suburban homes. At Churchgate, he would meet with likeminded seekers of the stardust, and while away the evening. Among them was his old friend, Subhash Ghai.

‘We came with different dreams,’ Subhash Ghai said, of those days of waiting. ‘I hoped to be a hero, he wanted to sing playback in movies. That was in the late 1960s. Mukesh, Rafi…were all at the top, even Kishore Kumar who had been singing for years had yet to find himself on par with them. There was little room for a newcomer. I asked him, “Why playback?” He retorted, “Why hero!” I think we both laughed, though our hearts were heavy with no sight of a breakthrough.

‘We would meet in front of Gaylords. So many of us hopefuls. We would walk the stretch of pavement, stop for tea at Asiatic which was a restaurant at that time. Then we would walk to the promenade and stroll by the sea. Sometimes we would spot a celebrity at Gaylords. It was a popular haunt for filmy people. Jaikishen would often be there. And we would see Jaidev. The place attracted all kinds of genteel people, who would sit in the semi-covered area sipping ice-cream floats and cold coffee from tall, slender glasses and eating chicken patties. They had the power to make dreams come true, but we seldom got a second look.’

Sometimes, the group would stop at Berry’s on the same stretch of road. Jagjit Singh too acknowledges the kindness he received in those difficult days. ‘Our patron and guide was Mr Berry, the owner of the restaurant of the same name. He used to allow me to eat there for free and was very helpful.’

Subhash Ghai would be among those watching his friend very carefully. Tracing his graph as he moved towards finding his own space. ‘I know that Jagjit finally found a foothold in the city. He started performing at some music club functions, at some annual gatherings of clubs. He could be very funny, and his repertoire included bawdy Punjabi songs that he sang with gusto. Yet he had a gentle side that could seduce the listener. When in college he would belt out the entire repertoire, including Saigal songs. I would join him in those, as I loved them too. Later, when he started singing ghazals, I was shocked! His style and quality were on par with Mehdi Hasan, at a level beyond imagination.’

Also in the group was another young man from the Punjab. A fellow Sikh who hoped to spin music for movies one day. Kuldeep Singh would later win acclaim for the music of Saath Saath.

‘I knew him as a fellow struggler. We were a few months apart in age. I was doing my MA in KC College at Churchgate, and we had our adda outside Gaylords every evening. We were a group of lost souls, who would stand outside and trade our day’s experiences. I knew Jagjit Singh because at some point we had shared a stage at some function. We had got talking then, and a friendship developed. We had a common joke. I would tell him, “When I get my chance as a music director, you will sing for me?” And he would say, “Just let me get my chance in a film, and I will get you on to make the music for it.’ I would stop for a paan, sometimes, and if he happened to pass by he would call out, ‘Where is my chance, when is it coming?’ It was all talk in the air… The hopefulness of the hopeless.’

Their camaraderie involved keeping one another’s morale high, and helping where they could.

Jagjit Singh was luckier than most. Jimmy Narula, who worked with HMV, who often joined the group arranged an audition for his friend.

Jagjit had been in the city for all of six months when this break came.

In a CD titled Rare Gems that traces the musical journey of Jagjit and Chitra Singh, there is a song that goes Saqiya hosh kahan tha. It follows another ghazal, Apna gham bhool gaye. Listen to both one after the other, and it is clear that in the space of that one recording, Jagjit Singh took a decision about his career. The two ghazals were on one side of the singer’s first recording with HMV in the form of an EP or Extended Play. Two songs by another singer, Suresh Rajvanshi, made up the other side. Music for all the songs was composed by CK Chavhan. In ‘Apna gham bhool gaye’, Jagjit adopted the style of Mukesh, who had given quite a few hit songs at the time and was top of mind for fans, but the second song was in Jagjit’s own style. He was casting the dice and hoping to be accepted. In his secret mind, he must have prayed that the song in his own style would prove the more popular.

The EP would add another twist to the flow of his life. Preparing for the release of the record, Jagjit took a sudden decision.

‘I was told to take a picture of myself. I still had my long hair, my beard and turban, and that was when I decided to cut my hair. I knew then, whatever picture was taken, that was how I had to remain for the rest of my career, so I felt it was better to cut my hair. ‘Are you sure,’ asked the barber. “Yes”, I replied, and that was it, my hair was cut.’

When he presented himself that evening to sing at a wedding reception, as he had been contracted to do, it took a lot of persuasion before he could convince those concerned that he was indeed the singer for the evening’s entertainment!

The decision did wonders for his image, showing off his clean-cut features, bringing the focus to his lips when he enunciated his music, laden with meaningful words. But it would almost put an end to his connection with his father, who would not brook this step that went against Namdhari Sikh tenets!

An extract from Baat Niklegi Toh Phir: The Life and Music of Jagjit Singh by Sathya Saran; published by Harper Collins

Find all the works of Sathya Saran here.

No Comments