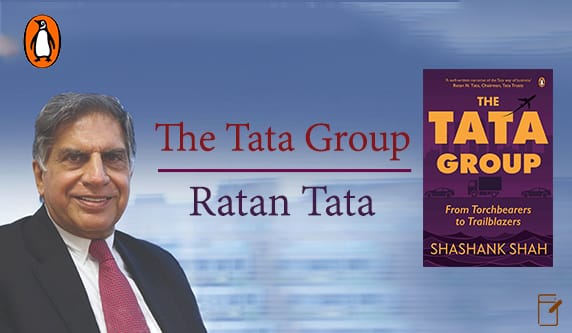

Padma Vibhushan, Ratan Tata is the Bharat Ratna personified.

Born in 1937, Ratan Tata hails from the famous Tata family, which got recognition under the guidance of his great-grandfather Jamsetji Tata, who later founded the Tata Group. He is an alumnus of the Cornell University College of Architecture and Harvard Business School through the Advanced Management Program that he completed in 1975. Ratan Tata joined his company in 1961 when he used to work on the shop floor of Tata Steel, and was the apparent successor to J. R. D. Tata upon the latter’s retirement in 1991.

Ratan Tata’s arrival coincided with the liberalization of Indian economics. The stage was set, also the lieutenant was ready to take the charge. With his relentless efforts, a young Ratan Tata got Tata Tea to acquire Tetley, Tata Motors to acquire Jaguar Land Rover, and Tata Steel to acquire Corus, in an attempt to turn Tata from a largely India-centrist group into a global business.

A Tale of a billion strong people

The tale of the Tata Group is the tale of a young nation that weathered many storms and succeeded to find its voice on the global stage. n the last 15 decades, the Tata Group has continually risen into becoming India’s largest global conglomerate – that it is today. The Tata tale is, indeed, quite synonymous with India’s industrial growth story.

It’s the tale of perseverance, ambition, discipline, intellect, foresight, and most importantly, business ethics.

The Tata Group is India’s largest private-sector employer that also has the largest customer base in India which is over 6.5 crores. Every Indian consumes some Tata product or the other, most popular being Tata salt.

The Tatas, another enigma?

But like many success stories in India, the story of the Tatas, too, remains somewhat of an enigma. The reverence we show to our ‘heroes’ deifies them with time and lifts them above the plane of mortals and wraps them in a shroud of mystery.

To clear this fog of magical realism and bring some method to the madness or more like the humanity of the Tatas, Dr. Shashank Shah brought out his wonderful book on the Tata group.

In his latest book, The Tata Group: From Torchbearers to Trailblazers, visiting scholar at Harvard Business School, and fellow and project director at Harvard University, Dr. Shashank Shah has meticulously researched India’s largest global conglomerate.

The Tata Group: From Torchbearers to Trailblazers

With over 100 companies offering products and services across 150 countries, 700,000 employees contributing revenue of US $ 100-billion, the Tata Group is India’s largest and most globalized business conglomerate. The Tata name is known for salt, software, cars, communications, housing, and hospitality.

How did they come so far?

How did they groom leadership, delight customers, and drive business excellence?

How did they maintain a brand and corporate values that are considered gold standard?

A deep-dive into the Tata universe brings forth hitherto lesser-known facts and insights. It also brings you face-to-face with business decisions and outcomes that are most intriguing:

– How did Tata Motors turnround Jaguar Land Rover when Ford failed to do so?

– Why wasn’t TCS listed during the IT-boom?

– Why wasn’t Tata Steel’s Corus acquisition successful?

This definitive book tells riveting tales and gives insider accounts of adventure and achievement, conflict and compassion, dilemmas and decisions across twenty-five Tata companies. With over a decade of rigorous research, interviews with 100 senior Tata leaders, and pan-India site visits, this book decodes the Tata principles of business. It’s an exceptional blend of a business biography and a management classic.

In an official author interview, Dr. Shah mentioned some interesting anecdotes.

“Let me share three – one from the post-liberalization era, one during the License Raj, and another during the British Raj. Through each of them, you will see a common thread of Tata-ness in decision making. When Tata Tea decided to exit from the plantation business in the 2000s, and transition to the branded tea and retail business, it wasn’t willing to exit its plantations before a sustainable model of livelihood was chalked out for its plantation workers. For this, Tata Tea had three strategic options. One was an outright sale to another company. This was the option selected by its competitor—Hindustan Unilever (HUL). McLeod Russel India, the world’s largest tea producer, had picked up HUL’s seven tea estates in Assam. Given that Tata Tea’s plantation earnings were in red, the new company would most likely slash wages, shut down social welfare programs, and even relieve thousands of employees. So, Tata Tea decided against it. The second option was to close the plantations. This would again lead to loss of livelihoods for over 13,000 employees working on those plantations, some of whom were third-generation workers. The company ventured for the third option, which involved divesting control to its workforce. It was a first-of-its-kind experiment in the world, at least in the tea plantation business.

Given that plantation workers were no longer Tata employees, but its suppliers, a prudent decision would have been to absolve itself from investments in existing employee welfare programs. Over the years, Tata Tea had invested substantial amounts in providing health and education facilities to its plantation employees. Logically, with the formation of a new company, the responsibility of managing these should have been transferred to the new management as the quantum of annual investment was nearly ₹20-crores – not a meager sum. This included a 150-bed secondary care general hospital, a school for employees’ children, and four vocational institutes for workers’ children with disabilities. When this matter was discussed with the then vice-chairman of the company, his answer was, ‘Continue, whatever it takes.’ And so Tata Tea continued to spend ₹20-crores every year on the social welfare projects of a company that was now its supplier!

In the late-1980s, Taj Hotels had suspended two employees on charges of theft. Post an inquiry process, the charges were upheld, and their services terminated. They made several appeals, one of which was to J.R.D. Tata, the Tata Group Chairman. On the morning of the day, he completed 50 years as chairman of Taj, J.R.D. spent an hour reading the inquiry proceedings and questioning the main witness. He told the concerned Taj manager, ‘I am satisfied that you have been fair. Go ahead and terminate them, but please see if we can do something for their families, especially if they have school-going children.’ The octogenarian J.R.D. did not want the kids to suffer because of their fathers’ follies.

In 1922, Tata Steel was on the verge of closure as its profits plummeted thanks to the British Raj’s antithetical reciprocation to Tatas’ magnanimity. The Tatas had supported the British Raj during World War I by fulfilling war-related product requirements instead of more profitable commercial products. However, in the post-war years, the Raj opened up the market leading to low-cost steel dumping from Europe and Asia severely affecting Tata Steel’s profitability. Some investors suggested that Tata Steel be sold off. ‘Over my dead body’, thundered R.D. Tata (father of J.R.D. and one of the four founders of Tata Sons). To salvage his father’s dream and the Tatas’ flagship company, Sir Dorabji Tata (Jamsetji’s son) pledged his personal wealth of ₹1 crore, including his wife’s jewelry and the Jubilee Diamond (twice the size of the Koh-i-Noor), and raised a loan from the Imperial Bank of India (now State Bank of India) to pay salaries and remain afloat. This is contrasting to contemporary times when corporate leaders secure pay-rises for themselves when their companies are bailed out through governmental support and taxpayers’ munificence – both in India and especially overseas (during the financial crisis of 2008). The likes of Nirav Modi and Vijay Mallya who enjoy luxurious lives while their employees pay a heavy price for their failed businesses have a lot to learn from the Tata way of business. It isn’t limited to the case of Tata Steel in 1922, Jamsetji did the same for the Swadeshi Mills in 1880s and Ratan Tata for Tata Finance in the 1990s, and Tata Teleservices in 2017.”

We, at MarkMyBook, wish Ratan Tata a very happy birthday and a healthy year ahead.

No Comments